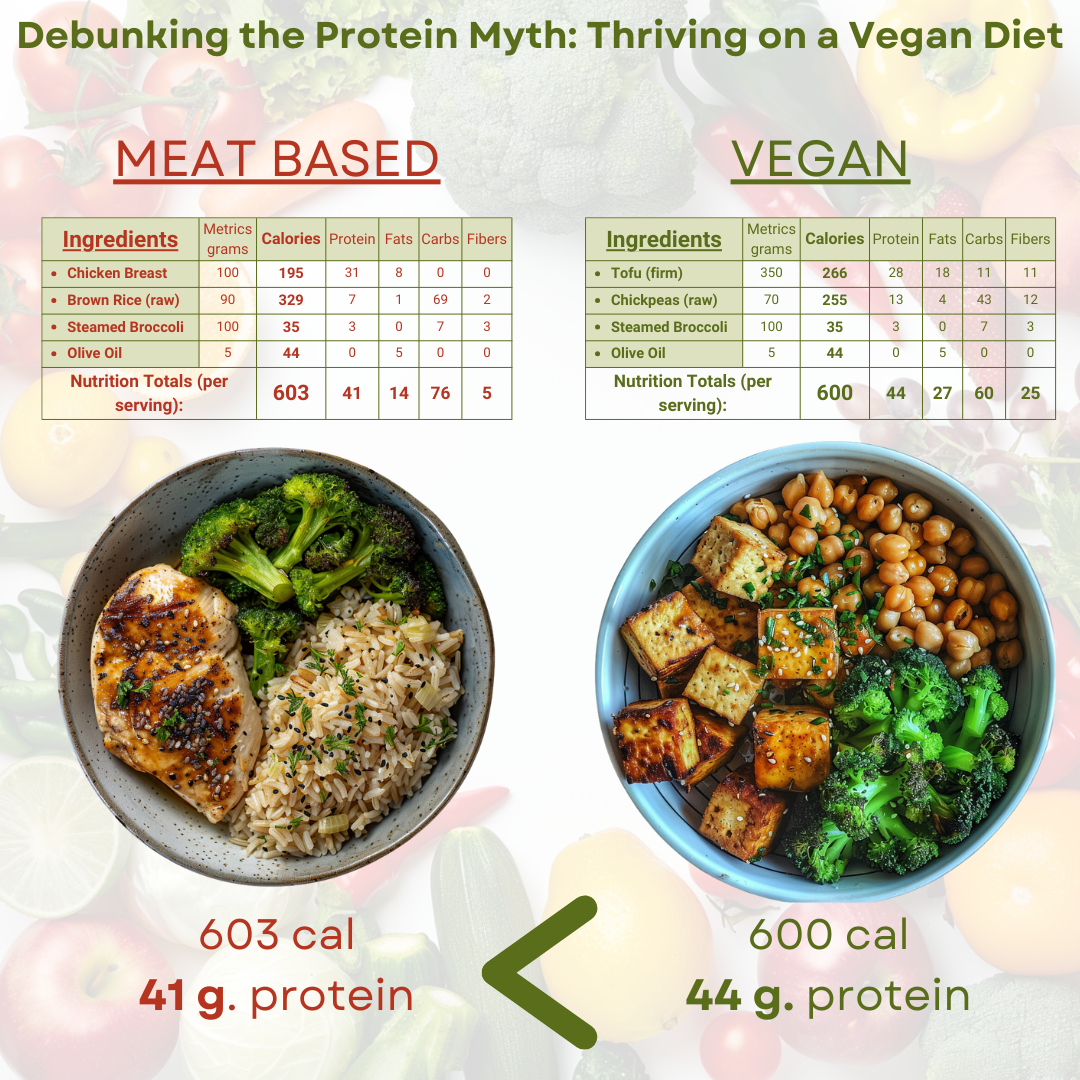

As veganism gains popularity, many athletes are turning to plant-based diets to meet their nutritional needs. One of the primary concerns for these athletes is how to consume enough protein to support muscle growth and maintenance without animal products. This article delves into the scientific aspects of vegan protein sources and provides practical guidance for athletes aiming to build muscle on a vegan diet.

The Science of Protein and Muscle Building

Protein is crucial for muscle growth and repair. When we engage in resistance training or other forms of exercise, our muscles undergo microscopic damage. Protein provides the amino acids necessary to repair and rebuild these muscle fibers, making them stronger and larger over time.

Protein Requirements for Athletes

The general recommendation for protein intake is 0.8 grams per kilogram of body weight for the average adult. However, athletes, particularly those involved in strength training, often require more. Studies suggest that athletes may benefit from 1.6 to 2.2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight per day to optimize muscle protein synthesis and support recovery.

Muscle Protein Synthesis and Vegan Protein

Muscle protein synthesis (MPS) is the process through which new muscle proteins are produced, leading to muscle growth. MPS is regulated by various factors, including protein intake, exercise, and the availability of amino acids. Leucine, an essential amino acid, plays a particularly significant role in stimulating MPS. Animal-based proteins typically have higher leucine content compared to most plant-based proteins, but vegan athletes can still achieve optimal MPS through strategic dietary choices.

Combining Protein Sources for Optimal Amino Acid Profile

While many plant-based proteins are incomplete, meaning they lack one or more essential amino acids, combining different sources can ensure a complete amino acid profile. For instance, rice and beans together provide all essential amino acids, making them a complete protein source. Similarly, combining hummus (made from chickpeas) with whole-grain pita offers a balanced amino acid profile.

The Role of Essential Amino Acids in Vegan Protein

Essential amino acids (EAAs) are those that the body cannot synthesize and must be obtained through diet. There are nine essential amino acids, including leucine, isoleucine, valine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and histidine. For athletes, ensuring an adequate intake of these amino acids is critical for muscle repair and growth.

Leucine and Muscle Building

Leucine is a key player in initiating MPS. Research indicates that a threshold amount of leucine (approximately 2-3 grams per meal) is necessary to maximize MPS. While plant-based proteins generally contain less leucine than animal-based proteins, consuming larger quantities of diverse plant proteins can help meet this threshold.

Lysine and Methionine in Vegan Diets

Lysine is often considered the limiting amino acid in many vegan diets, as it is found in lower quantities in most plant foods compared to animal products. However, legumes, such as lentils and chickpeas, are excellent sources of lysine. Methionine, another essential amino acid, is relatively low in certain plant proteins but can be obtained from foods like sesame seeds, Brazil nuts, and soy products.

Digestibility and Bioavailability of Vegan Protein

Digestibility and bioavailability are crucial factors in determining how effectively the body can use the protein consumed. Plant proteins often have lower digestibility compared to animal proteins due to factors like fiber content and anti-nutritional compounds (e.g., phytic acid, tannins).

Enhancing Digestibility of Plant Proteins

Several methods can improve the digestibility and bioavailability of plant proteins:

- Cooking: Cooking legumes and grains can reduce anti-nutritional factors and improve protein digestibility.

- Soaking and Sprouting: Soaking beans and seeds before cooking, or sprouting them, can increase the availability of amino acids and reduce anti-nutritional compounds.

- Fermentation: Fermented foods like tempeh and miso have higher protein digestibility due to the breakdown of complex compounds during the fermentation process.

Addressing Common Concerns

Protein Quality

One concern about vegan protein is its quality compared to animal-based protein. While it’s true that most plant proteins are incomplete, a well-planned vegan diet that includes a variety of protein sources can provide all essential amino acids. Additionally, some plant-based proteins, like soy and quinoa, are complete on their own.

Digestibility

Plant proteins can sometimes be less digestible than animal proteins due to their fiber content and anti-nutritional factors. However, cooking methods, such as soaking, fermenting, and sprouting, can enhance the digestibility of plant proteins.

Enhanced Science Analysis of Vegan Protein and Muscle Building

Protein Quality and Digestibility: A Closer Look

The quality of protein is often measured by its amino acid composition and digestibility. The Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) and the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS) are two metrics used to evaluate protein quality. Animal proteins generally score higher on these scales due to their complete amino acid profiles and higher digestibility. However, plant proteins can still be highly effective for muscle building with the right combinations and preparation methods.

PDCAAS and DIAAS: Comparing Vegan and Animal Proteins

- PDCAAS: This method evaluates protein quality based on human amino acid requirements and digestibility. Proteins like casein (milk protein) and soy protein isolate score close to 1.0, indicating high quality. Most legumes score between 0.6 and 0.7, while grains typically score lower.

- DIAAS: This newer method considers the digestibility of individual amino acids, offering a more nuanced view of protein quality. Dairy proteins often score above 1.0, while soy and pea proteins have relatively high scores among plant-based options.

Leucine Thresholds for Muscle Protein Synthesis

Leucine plays a pivotal role in stimulating MPS. Research shows that consuming 2-3 grams of leucine per meal can maximize MPS. Given that plant-based proteins generally contain less leucine than animal-based proteins, vegan athletes need to be mindful of their total protein intake and meal composition.

For example:

- Soy protein: Contains about 8% leucine.

- Pea protein: Contains about 8-9% leucine.

- Brown rice protein: Contains about 8% leucine.

To meet the leucine threshold, a vegan athlete might need to consume larger portions or combine multiple protein sources to ensure adequate leucine intake.

Impact of Anti-Nutritional Factors

Anti-nutritional factors in plant foods, such as phytic acid, tannins, and lectins, can inhibit nutrient absorption and protein digestibility. These compounds can bind minerals and proteins, making them less available for absorption. However, several preparation methods can reduce these anti-nutritional factors:

- Soaking: Soaking beans and grains before cooking can significantly reduce phytic acid content.

- Sprouting: Sprouting seeds and legumes can enhance the bioavailability of nutrients and reduce anti-nutritional compounds.

- Fermentation: Fermented foods like tempeh and miso have improved digestibility and nutrient profiles.

Long-Term Adaptation to a Vegan Diet

Research suggests that individuals who follow a vegan diet long-term may experience changes in their gut microbiota that improve their ability to digest and utilize plant-based proteins. The gut microbiota adapts to the diet, increasing the population of bacteria that help break down fiber and other complex plant compounds.

Gut Health and Protein Absorption

A healthy gut microbiota can enhance overall nutrient absorption, including protein. Consuming a diet rich in fiber, prebiotics, and probiotics can support a healthy gut environment. Foods like sauerkraut, kimchi, and kombucha provide beneficial bacteria that can aid digestion.

Protein Intake and Distribution for Optimal Muscle Growth

Distributing protein intake evenly throughout the day can help maintain a positive nitrogen balance and support continuous muscle protein synthesis. For vegan athletes, this means including a source of protein in every meal and snack. Research indicates that consuming protein every 3-4 hours can be beneficial for muscle growth.

Post-Workout Nutrition

Post-workout nutrition is critical for muscle recovery and growth. The “anabolic window” refers to the period immediately after exercise when the body is particularly receptive to nutrients. Consuming a protein-rich meal or shake within 30-60 minutes post-exercise can maximize muscle protein synthesis and glycogen replenishment.

The Environmental and Health Benefits of Vegan Protein

Beyond muscle building, choosing vegan protein sources has several environmental and health benefits. Plant-based diets are associated with lower risks of chronic diseases, such as heart disease, diabetes, and certain cancers. Environmentally, plant-based proteins have a lower carbon footprint and require fewer resources, such as water and land, compared to animal-based proteins.

Success Stories of Vegan Athletes

Many successful athletes thrive on vegan diets, debunking the myth that animal protein is necessary for peak performance. Notable vegan athletes include:

- Patrik Baboumian: A strongman competitor who holds several world records.

- Venus Williams: A tennis champion who credits her vegan diet for her sustained energy and recovery.

- Kendrick Farris: An Olympic weightlifter who has achieved remarkable feats on a vegan diet.

Conclusion

Building and maintaining muscle on a vegan diet is entirely achievable with proper planning and knowledge. By incorporating a variety of plant-based protein sources and ensuring a complete amino acid profile, vegan athletes can meet their protein needs and excel in their sports. The shift towards vegan protein not only supports personal health and performance but also contributes to a more sustainable and ethical food system.

By focusing on diverse vegan protein sources and strategic meal planning, athletes can harness the power of plant-based nutrition to fuel their fitness goals effectively. Through understanding the science behind protein digestion, amino acid profiles, and the benefits of plant-based diets, vegan athletes can confidently pursue their muscle-building goals.

References

- Phillips, S. M., & Van Loon, L. J. C. (2011). Dietary protein for athletes: From requirements to optimum adaptation. Journal of Sports Sciences, 29(sup1), S29-S38.

- Morton, R. W., Murphy, K. T., McKellar, S. R., Schoenfeld, B. J., Henselmans, M., Helms, E., … & Phillips, S. M. (2018). A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of protein supplementation on resistance training-induced gains in muscle mass and strength in healthy adults. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 52(6), 376-384.

- Wolfe, R. R. (2017). Branched-chain amino acids and muscle protein synthesis in humans: myth or reality? Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 14(1), 30.

- Mariotti, F., & Gardner, C. D. (2019). Dietary protein and amino acids in vegetarian diets—A review. Nutrients, 11(11), 2661.

- Berrazaga, I., Micard, V., Gueugneau, M., & Walrand, S. (2019). The role of the anabolic properties of plant- versus animal-based protein sources in supporting muscle mass maintenance: A critical review. Nutrients, 11(8), 1825.

- Tome, D. (2012). Criteria and markers for protein quality assessment–a review. British Journal of Nutrition, 108(S2), S222-S229.

- Devries, M. C., & Phillips, S. M. (2015). Supplemental protein in support of muscle mass and health: advantage whey. Journal of Food Science, 80(S1), A8-A15.

- Gorissen, S. H., & Witard, O. C. (2018). Characterising the muscle anabolic potential of dairy, meat and plant-based protein sources in older adults. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 77(1), 20-31.

- Hoffman, J. R., & Falvo, M. J. (2004). Protein–which is best?. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 3(3), 118.

- Rutherfurd, S. M., & Moughan, P. J. (2012). Available lysine in foods: A review. British Journal of Nutrition, 108(S2), S77-S87.